Experienced UIUC graduate student specializing in Math, Computer Science, and Writing

Availability:

Every day, 10:00am-10:00pm PST

Subjects:

Math

Computer Science

Writing

Finland's Education System Succeeds Because of Equity and Diversity

Last Updated:

- While most Americans are dissatisfied with the quality of US public education, Finland's education is highly praised for a very different structure.

- Many teachers complain about worse behavioral issues and stunted social skills as a result of the disruption to student lives

- The relief funds provided by the federal government are expiring September 2024, so many efforts to fix achievement gaps will no longer continue

In the US, there are often huge disparities between rural, suburban, and urban schools.

Many suburban schools in the Bay Area, like Amador Valley High School and Foothill High School, rank in the top 1% of schools in the country according to GreatSchools rankings. We can see the same patterns in Palo Alto, Cupertino, and other cities known for a high concentration of competitive students and workers in peaceful suburbs. A big part of this is parental involvement, as families that are highly educated have the means and will to provide a secure, resource-filled environment for their children when schools might fall short. They’re in direct proximity of highly desirable jobs and companies eager for talent.

As high-paid skilled workers of growing companies flock to communities with these schools for their kids, they drive property values up. In the US, school funding is heavily tied to local property taxes, so schools in highly desirable suburbs like the Tri-Valley benefit from this funding model.

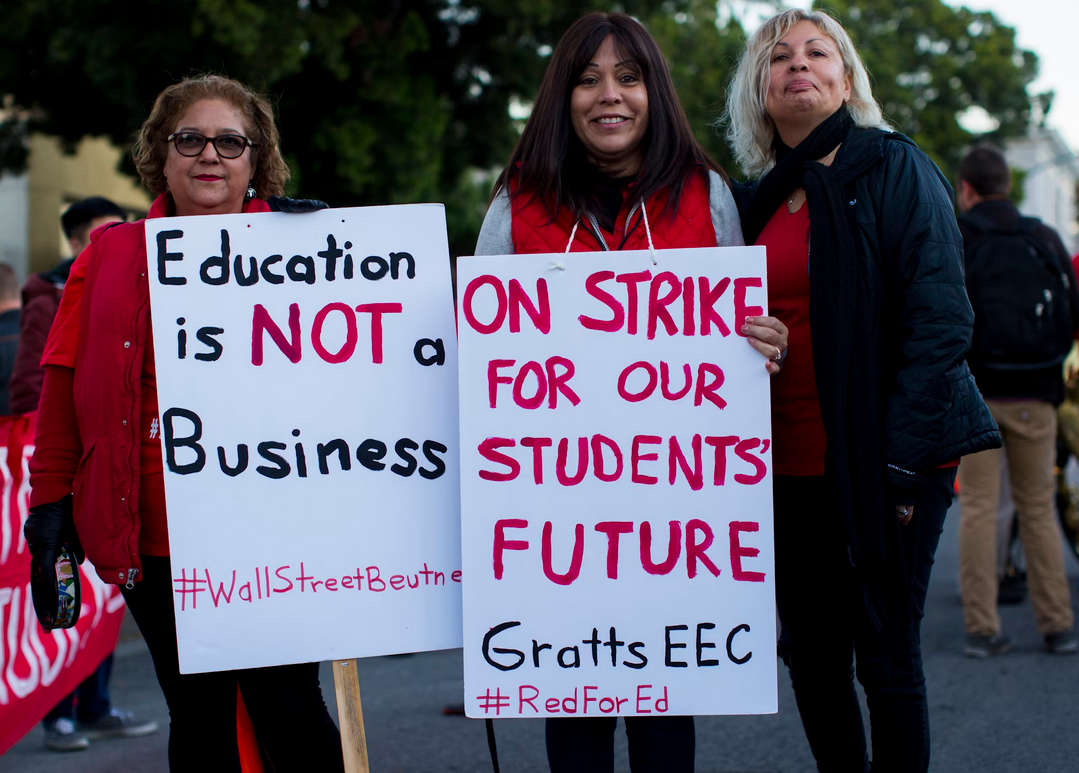

On the other hand, rural and inner city schools are a political football used every election cycle, always seemingly in a crisis or three. There are fewer resources because of the property taxes-based funding structure. Teachers may be stretched thin doing work like coaching and counseling because of the smaller labor pool. They’re further away from colleges and their alumni networks, so the influence of higher education and cutting-edge industry is diminished.

However, recently 45% of Californians in the San Francisco Bay Area feel that education is heading in the wrong direction and only 13% believe it’s heading in the right direction. There’s increasing dissatisfaction with schools even in suburban regions, in part due to teacher shortages, more competitive environments, and worsening achievement gaps after COVID.

As we examine the directions we can go, we should consider looking at the systems other countries have implemented. Finland has long been considered the goal standard of education systems with excellent student performance, minimal stress and busywork, prestige within teaching, and no standardized testing. Given the turbulence and inequalities in the US education system, it’s worth identifying one of the core principles that Finland adheres to that we do not.

Emphasis on Equity

After WWII, Finland was shifting rapidly from an agrarian society to an industrialized one, which required widespread educational reform. Early systems separated students into academic and vocational tracks by their ability at an early age. They often neglected a student’s growth, interests, and well-being, and so they deepened inequalities in Finnish life and reserved access to higher opportunities to the elite. Defenders of this system believed in fixed mindset ideas, so they thought students from different social and intellectual backgrounds couldn’t all succeed by the same expectations.

These were replaced by peruskoulu, a Finnish term for the comprehensive school system covering grades 1-9 for children ages 7-16. It literally translates to “basic school” and heavily incorporates ideas built on growth mindsets. This system was built on emphasizing equity, so that students receive a high-quality education regardless of where they teach. While this sounds like a difficult constraint for education quality, it actually helped the Finnish system develop a strong sense of social justice. Student performance is consistent across the country because the added focus of social issues allowed for flexible lessons tailored for different cultural environments and promoted student well-being holistically.

Finland, instead of relying on property taxes and local funding, funds every school from its central government, so regional wealth is not a factor in determining the quality of education. This means rural schools in Finland get the same educational materials, technology (including Internet connection), free school lunches, healthcare, transportation, and infrastructure as urban and suburban ones. With this principle, programs and solutions are designed with every type of student and environment in mind instead of just those that politicians favor at some point in time.

Finnish teachers are held to the same standards of at least a Master’s degree everywhere instead of a state-by-state system that the US uses. Sometimes this leads to fewer teachers available, but the government offers support for accommodations like multi-age classrooms.

Why Not Cheat and Copy-Paste Finland’s Work?

When you have two complex systems with a lot of differences in their fundamental principles, copying policies can be extraordinarily difficult or ineffective, if even possible.

The education system of the US has always been decentralized across states, countries, and cities. We do have the Department of Education to provide grants, protect rights, and help with some coordination between states, but schools are still heavily dependent on property taxes which is a localized power. Switching to a model where the DoE funds every school would be a difficult transition to make, especially when some politicians argue for cutting the DoE altogether.

Further, many of the changes Finland made were outside of what the US considers educational policy issues. Finland has understood that education systems don’t succeed in isolation from strong social welfare policy and robust infrastructure. Wi-Fi access, public transportation, remote learning support, technology infrastructure, free university to accompany higher standards, and early intervention from psychological counselors are key features of the Finnish system.

We should also acknowledge that Finland has a more homogeneous culture and society than the US, which is built on large waves of immigration that formed communities and subcultures and has many different economies based on regionalized trends in natural resources and climate.

But we can still make progress

It might not be as simple as it seems to implement some of Finland’s policies in the US, but we can certainly learn from their direction.

We don’t have guaranteed secure, nutritious school lunch programs. Wi-Fi can be great in some schools but nonexistent in others. Colleges and Universities have insanely high tuition rates that continue to grow, without any meaningful improvement to the quality of life or educational experiences students have. Public transport is a nightmare, as America is very car-centric. Early intervention in case of learning, behavioral, or mental health conditions is considered a luxury for schools here. Most counselors will never get personal time with their students to connect and assist.

Even if we need to take radically different approaches than Finland, we can at least identify these problems and the direction of our solutions: towards improving equity and valuing every child’s right to an exceptional education.

As a tutor who has taken online sessions, I’ve talked to students from other countries who discuss educational environments that look very different from the US, including the Tri-Valley. I’ve seen how students who are happy with their schools, teachers, and peers have strong alignments between their motivations and educational success.

While it might take time for reforms to be implemented in policy, we as tutors borrow new ideas from different places all the time if we think it will help you. Reach out to us if you’re looking to improve your approach or discover a new one!

Related Articles

CA Prop 2: Borrowing $10 Billion to Repair Public Schools

Remote Learning is a Game-Changer for Global Education

Pleasanton Mayoral Candidates Square off Over 10 Key Issues

UN Initiatives Paint Optimistic Picture For Girls' Education